Papers, Please does a better job than a lot of movies (perhaps by virtue of you, the player, having some control over the direction of the story) at portraying the banality and dare I say violence of a totalitarian system. Set in a dystopian Communist country, Arstotzka, the player wins the ‘labour lottery’ and must now take a position at a border checkpoint in the recently partitioned border town of Grestin. After a six year long war with its neighbour Kolechia, and in a Berlin Wall situation, the checkpoint must be manned as waves of immigrants, visitors and others attempt to enter the country.

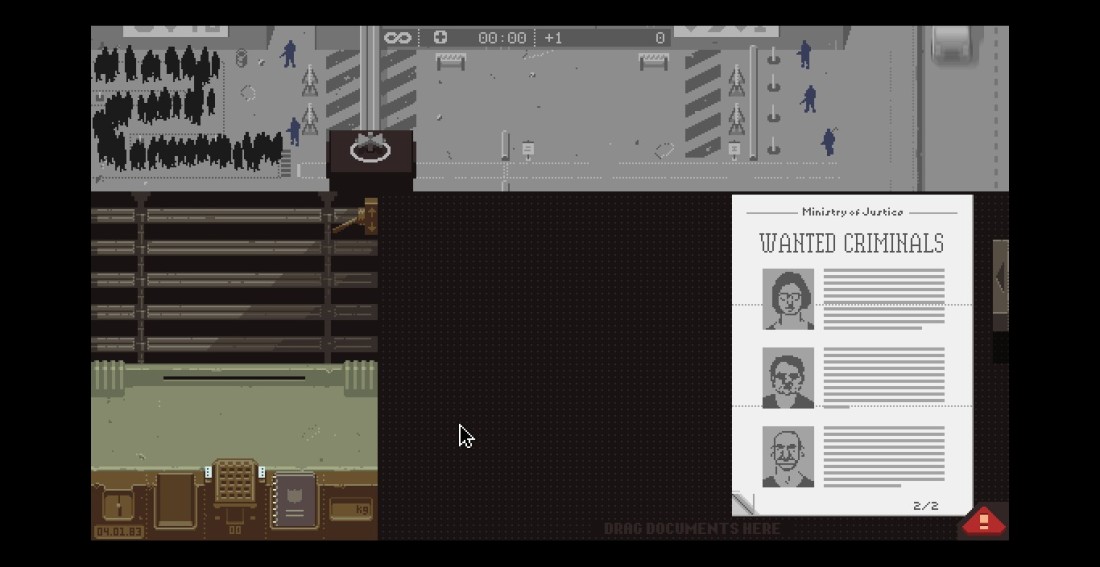

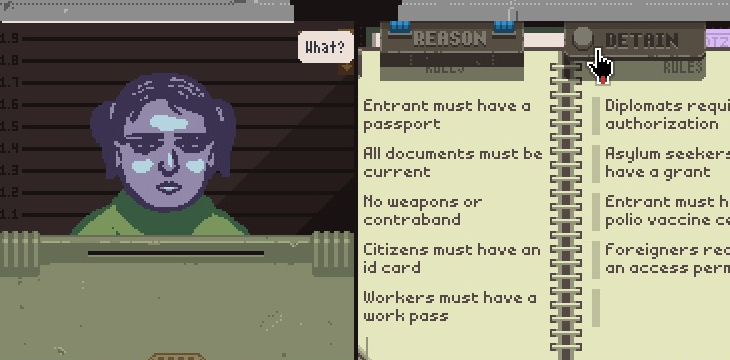

The game is elegantly balanced. Starting shifts early in the morning, the game constantly keeps you timed, rewarding you for processing as many passports as possible. However, hidden amongst these throngs of people are criminals: human traffickers, smugglers, terrorists. There are also those will far more menial concerns – that their passport or authorisation permit has expired, and all other manners of bureaucratic problems. You must be as fast as possible whilst making as few mistakes as possible, and each day you are paid. This money can be used to buy upgrades for your booth (so that you can inspect more passports quickly etc) or used to pay for food and heating. Make too many mistakes, and your son, mother in law or wife could easily die. The stakes are high.

The game places pressures on you to call the shots – you decide who goes in. And often, many who arrive at the checkpoint have heart breaking stories. Some beg to be let in to be reunited with their family. Some have been caught up in the arbitrariness of bureaucracy: one day the ID permit is perfectly acceptable, but today new documentation has been added, and so on. You can break the rules, and help out those in need. You can work with patrol guards who themselves get a bonus for the number of detainees they process, or with the terrorists and counter-revolutionaries who want to bring down the communist regime. Some immigrants who beg to be led in will sometimes refuse to leave the passport booth. Gruff guards enter, greet them with a rifle butt to the face and drag them away down an alley and in some horrible way, as the guard shares his detainee bonus with you, you have profited from whatever happened to that person.

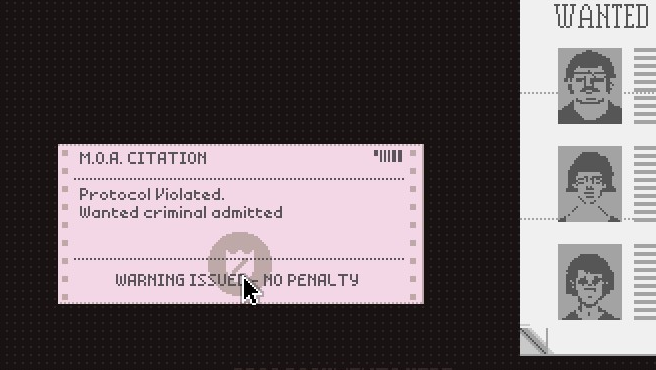

However, doing good isn’t simple either – there is always a cost for doing the ‘right’ thing. You receive fines for every wrongful entry, which can lead to being short on food or heating for the week, at worst spiral into your family falling ill or dying. If you don’t strike your own balance of working with the terrorists, then you will be caught up Stasi-esque authorities and punished. You can even go so far as to attempt to flee the country, but in doing so you must procure passports to make forgeries from – passports that can be (and usually are) obtained from completely innocent people.

This is the central conflict within Papers, Please. By placing you in the player in these shoes, we see demonstrated to us some of the finer points of Hannah Arendt’s points on the banality of evil, and Stanley Milgram’s study on obedience to authority. The game does not encourage you to think about the repercussions of your actions, in fact you are encouraged to view people only through their passport and ID papers, not as though they are people. The benefits of working within the system, to be a low level functionary in an immoral regime are quite clear, but at the cost of your own integrity and morals. In some sense, you get placed in a situation where you are just following orders. Papers, Please gives you ample choice. You can unquestioningly follow the regime without question, detaining and turning away immigrants, those seeking asylum and others for the most mundane and small bureaucratic errors. You have the power to decide who deserves to be in the country and who does not.

Despite the profoundly mundane nature of the game, it carries with it prescient messages, many of which are far from mundane. As border security becomes a larger concern in Britain, perhaps the game reminds us that a black and white view of ‘accept entry’ or ‘deny entry’ might not be deliberately monstrous, and even those who accept and deny are not evil or sadistic, but it can easily lead to all kinds of awful endings. In Papers Please, you don’t have to shoot anyone, or harm any physically to damage them: a simple red stamp might be a violent enough act to destroy someone’s life, as the game subtly reminds us. Though it is a game, perhaps we ought to take heed of this lesson in the real world…

References:

Can we reblog this for Heymillennials? If so could you spend a little less time describing the game and more on its context and the implications of complicity. Or, perhaps illustrate with examples of decisions you made during the game and their implications, making a sort of story out of it?

LikeLike

I would be happy to let you reuse this. If you like, I can spin it into a narrative about a typical ‘day’ or so at work, to change the emphasis away from description.

LikeLike